It was a hot morning at Cape Canaveral in Florida, on July 1st, 2023, two years ago today. It was the first morning of the 3rd quarter of the year, the earliest possible launch day for Euclid. Late at night there had been some last minute work on the launcher and at 3AM the rocket apparently had still been lying horizontally, but a few hours later it could be seen standing upright with Euclid on top, sheltered by an ESA- and Euclid-themed fairing. The launch was on!

A number of Euclid Consortium and ESA colleagues had travelled to Florida to experience this moment. Some people had been involved with Euclid for 15 or more years at that time. While rocket launches have become less of a sensation in the past decade, experiencing the result of one’s own work over many years sitting on top of hundreds of tons of flammable fuel was a good source for excitement and some anxiety. Would the launch take place today? Would it work without issues? Once on its way to Lagrange Point 2, would Euclid switch on, would it talk to us, would all instruments work? So many unknowns.

Kennedy Space Flight center overflowed with space exploration history. The Apollo/Saturn V exhibition gave a tangible impression of the race to the Moon but also around all the history of NASA and its space missions over the decades. It was humbling to know ‘our own’ space telescope in this company.

Outside the temperatures rose steadily, only bearable with ice-cooled water. Most Euclid people were attending the launch from the bleachers at the Banana Creek viewing area close to the Apollo exhibition, 10 kilometer from Space Launch Complex 40. A live moderator was explaining the mission to all other visitors that were there for the launch viewing – then also a direct stream from ESA was provided, live from ESA’s mission control ESOC in Darmstadt, Germany.

Then the clock moved towards 11 AM. The countdown started into the last minute, then the final 10 seconds. And the rocket simply lifted in the distance, only several seconds later the very loud rumbling – even at that distance – reached Banana Creek. The rocket accelerated near vertically, like everyone had seen in many videos before, but most of them never with their own eyes and ears. Here and now it was ‘our’ telescope, within minutes of becoming a proper space telescope.

The noise was intense. Noise from the launch meant vibrations that would shake the whole rocket and payload. These were the forces that Euclid would only experience for a few minutes, yet that had dominated the structural design process of most components for the past decade. We would soon see if all planning, building, and testing – involving the work by thousands of people over the years – had been sufficient.

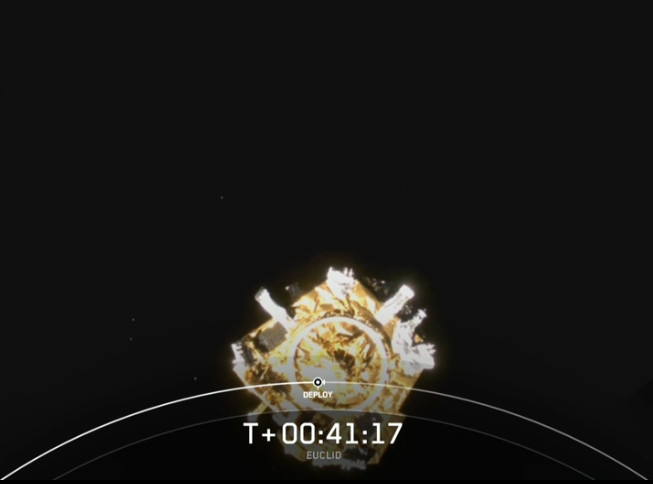

All of the launch was ‘nominal’, lingo for everything running according to plan. The rocket and Euclid survived the point of strongest vibrations, the point of strongest aerodynamic forces, first and second stage fired as planned. It was then a long, 45 minute wait, to see Euclid being inserted into its orbit towards L2 and to see ESOC confirming acquisition of Euclid’s communication signal. We had a space telescope, and we could talk to it!

In the days and weeks after launch several other milestones came and went, the spacecraft was fine, the instruments turned on and took first pictures and spectra. After several months of ‘commissioning’ startup and first calibration, where some initial bugs had to be ironed out, Euclid performed amazingly well. The instruments “just worked”, as was our short summary. Since then first Early Release Observations were taken and released to showcase Euclid’s power. Then in early 2024 we started Euclid’s sky surveys – with some needed intervention due to water ice contamination – and now? Well, Euclid continues to be “just working”.

Having released the first science-grade data in the Q1 data-release in early 2025, both ESA and the Euclid Consortium are working towards the first of three major public data releases, DR1, in October 2025. Euclid has already started taking data for DR2, the DR1 data are currently being processed into their final versions. Aside from this being an extremely complex task that many people have been working for since more than a decade, and that will take several more months to complete, Euclid is just continuing to survey the sky. 10 square degrees every day, 50x the visible size of the Moon.

These were big steps from having a mission ‘on paper’ after selection of Euclid by ESA in 2011, to having hardware that theoretically should work as a space telescope in June 2023, to having an actual space telescope after July 1st, 2023. Now, after two years in space, Euclid is producing unprecendented data that many scientists are already using to extract answers to fundamental questions in astronomy. New insights into Euclid’s core cosmology questions will take some more time. Euclid’s mission will continue for at least 4-5 more years – and after that we will see if the science community and ESA will find good projects (there is really no doubt about that), and funding, for a potential mission extension.

Right now, Euclid has come a long way since July 1st, 2023, yet this seems both like not so long ago but simultaneously it was a very different time. We are very curious what Euclid will have brought us in another two years from now, in 2027.

Links

Launch video: ESA

ERO images:

Batch 1: ESA

Batch 2 and science papers: ESA / EC Blog